Ghosts in the Machine - Mining the Near-Misses: How Saudi Arabia's NGD Legacy Data Is Pointing to the Next Generation of Discoveries

Over the past year, we've applied AI to Saudi Arabia's geological datasets to revisit exploration that stopped just short of understanding. This article synthesizes multiple studies to show how orphaned mines and near-misses can be reframed as signals, not failures.

Introduction

Saudi Arabia has one of the most ambitious mineral strategies in the world.

Critical minerals, national-scale geological datasets, and a clear mandate to accelerate discovery.

Over the past year, we've published a series of deep-dive articles exploring how AI can be applied to Saudi Arabia's National Geological Database (NGD) - from gold and graphite to MVT systems, porphyry copper, and regional outliers.

Each article focused on a specific question:

- How do you find signal in thousands of unstructured reports?

- How do you encode geological concepts, not just keywords?

- How do you surface overlooked prospects hidden in historical language?

But taken together, these studies point to a much larger insight:

Saudi Arabia's greatest untapped mineral opportunity may not lie in undiscovered terrain - but in undiscovered reasoning embedded in its exploration history.

Buried within NGD's bibliographic reports are decades of decisions, assumptions, failed hypotheses, and partial successes. Not just what was explored - but how, why, and where explorers stopped short.

This article ties those threads together.

It walks through what we've learned by analysing Saudi Arabia's legacy exploration archives as a learning system, and how that thinking is now shaping our work on orphaned mines, abandoned prospects, and critical minerals ahead of Future Minerals Forum.

The Saudi NGD Is Not a Database. It's a Memory

Most geological databases are treated as inventories.

- Coordinates.

- Commodities.

- Dates.

But Saudi Arabia's NGD bibliographic archive is something far more powerful - and far more underutilised.

It is a collective memory of exploration.

Each report captures:

- A geological model that was considered valid at the time

- The tools and techniques that were available

- The economic assumptions driving decision-making

- The moment where an explorer decided to continue - or walk away

When read individually, these documents look like static records.

When read collectively, they tell a dynamic story of how geological understanding evolved - and where it stalled.

This distinction matters.

Because most "missed" deposits were not ignored - they were approached with incomplete models, limited depth penetration, or commodity assumptions that no longer apply.

In Saudi Arabia, much of the historical exploration recorded in NGD was conducted:

- Before modern critical mineral demand

- Before current deposit models were mature

- Before high-resolution geophysics and geochemistry were widely deployed

As a result, many prospects were labelled:

- Uneconomic

- Sub-scale

- Anomalous but unexplained

Those labels persist - not because the geology changed, but because the reasoning never got a second pass.

Our work with Saudi NGD started with a simple question:

What happens if we stop treating reports as documents - and start treating them as evidence of geological thinking?

Answering that required moving beyond search, keywords, and summaries - and into synthesis.

Following the Clues: What Saudi's Exploration Reports Actually Revealed

Our work with Saudi Arabia's NGD did not begin with a grand theory.

It began with a practical frustration:

Important geological observations kept appearing - but never in the same place, format, or language.

Each case study we published focused on a different commodity or exploration question, but together they revealed a consistent pattern:

the signal was rarely missing - it was fragmented.

Gold: When the Evidence Exists, but the Context Is Lost

Our first deep dive into Saudi NGD focused on gold - not because gold is rare in the data, but because it is overrepresented.

What became immediately clear was that the challenge wasn't finding gold references. It was understanding why so many gold prospects stalled.

Critical observations were often buried in narrative descriptions:

- alteration mentioned without follow-up,

- structures noted but never tested at depth,

- anomalous results dismissed because they didn't fit prevailing models at the time.

This work highlighted a foundational issue:

keyword search surfaces mentions, but geology lives in relationships.

A Simple Guide to Finding Gold and Mining Data in Saudi Arabia's Geological Database

Graphite: Commodity Blindness in Historical Exploration

Graphite presented a different kind of problem.

Many of the most prospective descriptions never used the word graphite at all. Instead, they described:

- carbonaceous schists,

- metamorphic host rocks,

- conductivity anomalies explored for other targets.

These reports weren't wrong - they were written before graphite was economically relevant at scale.

By analysing how geologists described rocks rather than what they named them, we were able to surface patterns that had been invisible to commodity-driven searches.

This was the first strong signal that economic context, not geology, often determines what gets overlooked.

Unlocking Hidden Graphite Deposits: How AI Transforms Unstructured Geological Data for Exploration

MVT Deposits: Searching for Concepts, Not Commodities

Mississippi Valley-Type (MVT) systems pushed this idea further.

MVT-style mineralisation is rarely announced explicitly in reports. Instead, it appears as scattered clues:

- host lithologies,

- fluid indicators,

- alteration styles,

- pathfinder geochemistry.

In this case, success came not from searching for "MVT," but from encoding the language of the deposit model itself.

This study reinforced a key lesson:

The most valuable signals in historical data are often implicit - and only emerge when you search for geological reasoning, not labels.

Unlocking the Potential of Mississippi Valley-Type (MVT) Mineral Deposits: How AI Analyzes Unstructured Geological Data for Enhanced Exploration

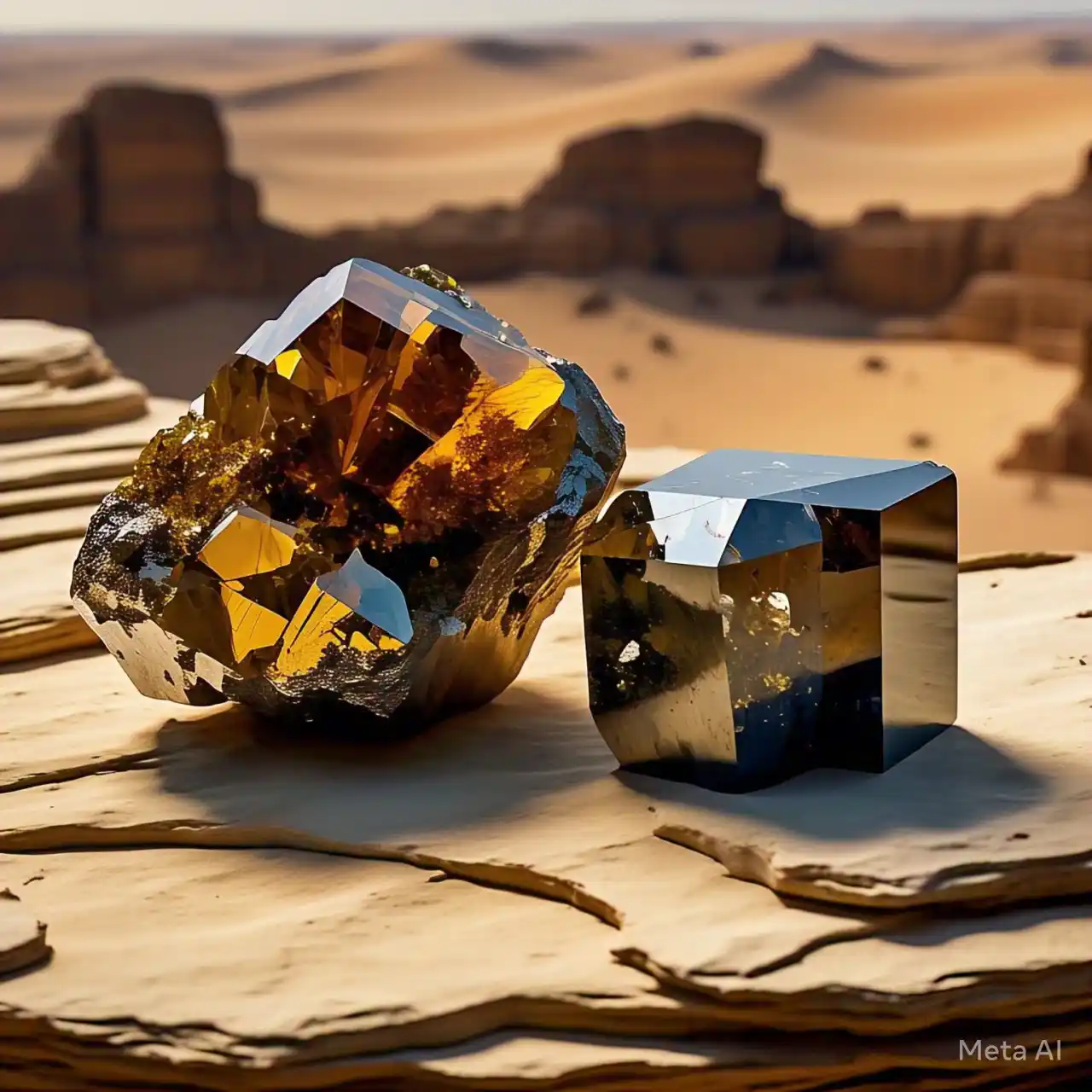

Porphyry Copper: When the Signal Exists Entirely in Text

Our porphyry copper work was a turning point, because it forced a simple question:

What if the strongest signal exists before any numbers are involved?

Rather than starting with geochemistry or geophysics, this analysis focused entirely on unstructured NGD bibliographic reports - the language geologists used to describe alteration, veining, intrusives, and structure.

What emerged was not a single "porphyry keyword," but a constellation of geological descriptions that repeatedly appeared together:

- alteration styles noted but not prioritised,

- intrusive relationships described cautiously,

- structural controls mentioned without a clear genetic model.

Individually, these observations were inconclusive.

Collectively, they formed a coherent porphyry-style narrative that was never explicitly labelled as such.

The insight here wasn't about prediction - it was about recognition.

The porphyry signal wasn't missing from Saudi Arabia's exploration history.

It was linguistically encoded - and fragmented across reports that were never read together.

Saudi Arabia's Next Copper Giant: How AI Reveals Overlooked Porphyry Clues in NGD Data

From Anomaly to Confidence: When Numbers and Narratives Agree

If the porphyry study showed how much signal lives in text alone, our work with Saudi Arabia's RGP / GCAS datasets exposed the opposite problem.

Structured geochemical data is excellent at highlighting what is unusual - but far less effective at explaining why it matters.

By applying anomaly detection to regional geochemistry, we identified patterns that stood out statistically but had never progressed into focused exploration targets. On their own, these anomalies were ambiguous: promising, but easy to discount without context.

From Outliers to Opportunity: Inferring New Mineral Targets with AI, RGP/GCAS Data and Saudi MODS

The real shift came when we asked a second question:

What did historical explorers say about these same areas - at scale?

By cross-referencing geochemical anomalies with tens of thousands of NGD bibliographic reports, we could see where:

- anomalous signals aligned with repeated geological observations,

- anomalies conflicted with historical interpretations,

- or were simply never followed up with the right model in mind.

This step transformed anomalies into something more meaningful - not answers, but confidence gradients.

An anomaly becomes actionable only when the collective geological record supports it.

This pairing of structured outliers with large-scale textual validation revealed how many opportunities sit in the space between interesting data and trusted interpretation.

When AI Meets 100,000 Geologists: Turning Hidden Clues into Mineral Targets

A Pattern Emerges

Across gold, graphite, base metals, porphyry copper, and regional geochemistry, the same failure mode kept surfacing.

It wasn't a lack of data.

It wasn't poor field observations.

And it certainly wasn't a lack of effort.

Exploration consistently stalled at the same point:

where information from different campaigns, data types, and eras needed to be synthesised into a single geological story.

Text described systems that numbers couldn't yet confirm.

Numbers flagged anomalies that text never reconciled.

And in many cases, each sat just one step short of the other.

The result was not false negatives - but unfinished interpretations.

Which raises a more uncomfortable conclusion:

Many of Saudi Arabia's "unsuccessful" exploration outcomes were not failures.

They were near-misses.

That insight demands a different way of thinking about historical data - and leads directly to the question of orphaned mines and abandoned prospects.

Orphaned Mines Are Not Abandoned Geology

In mineral exploration, "abandoned" is often treated as a geological verdict.

- Results are inconclusive.

- Budgets move on.

- The file is closed.

But our work with large national datasets suggests something more nuanced:

most exploration outcomes are abandoned for contextual reasons, not geological ones.

- Deposit models evolve.

- Tools improve.

- Institutional memory resets.

What remains behind is not failure - but unfinished reasoning.

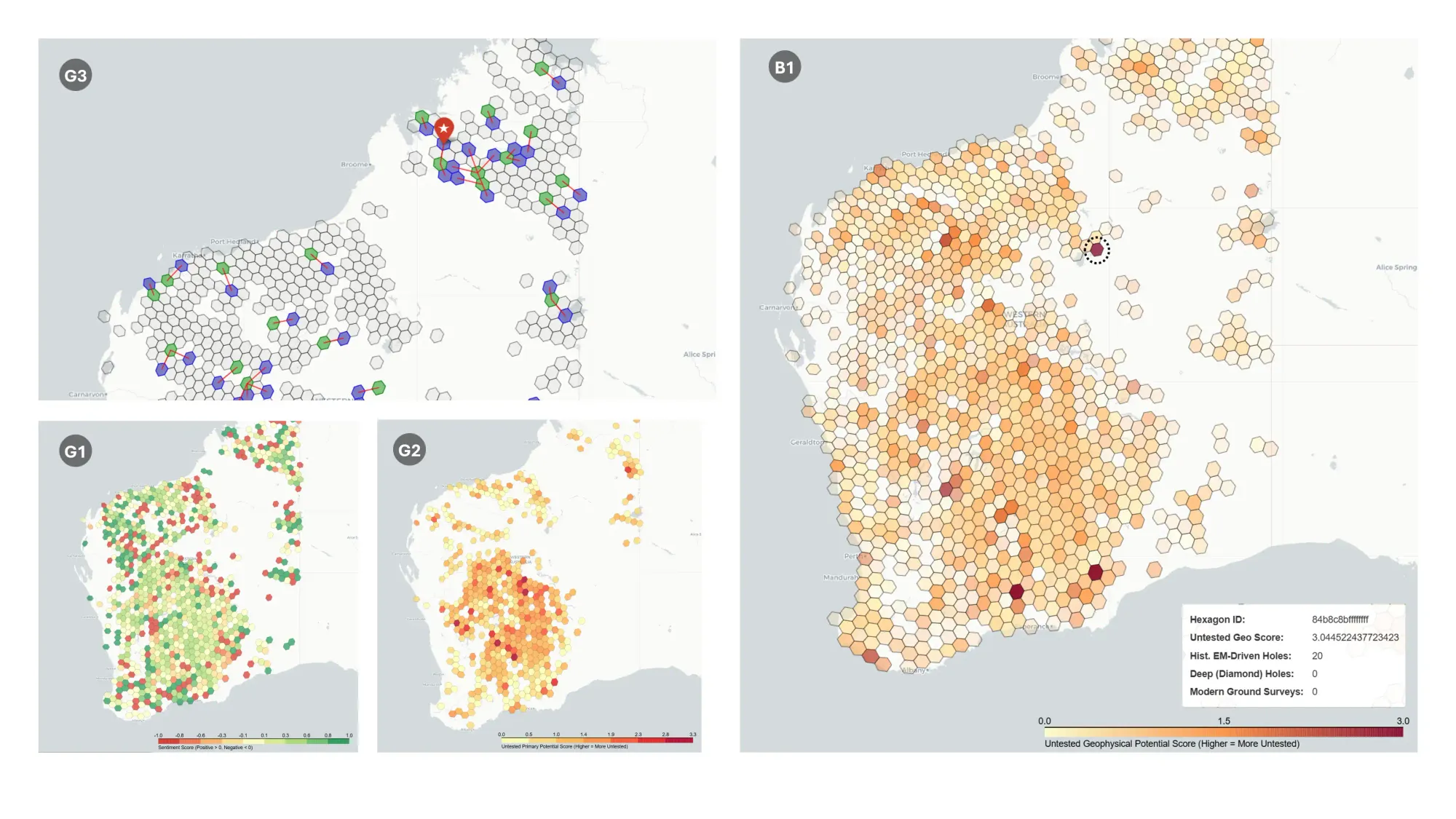

Redefining Failure: Lessons from Western Australia

This insight didn't originate in Saudi Arabia.

It emerged from our work in Western Australia, where more than a century of exploration activity is preserved in WAMEX - one of the world's most complete national exploration archives.

By analysing hundreds of thousands of historical reports, drill logs, and campaign summaries at scale, we stopped asking:

Where were discoveries made?

And instead asked:

Where did explorers come close - and why did they stop?

What we found was striking.

Large portions of Western Australia labelled as "unsuccessful" showed clear patterns of:

- repeated exploration with limited model variation,

- shallow drilling focused on specific historical paradigms,

- early termination just before major breakthroughs occurred elsewhere.

Failure, it turned out, was rarely random.

The Signature of a Near-Miss

Near-misses leave fingerprints.

They appear as:

- dense clusters of shallow drilling with little depth testing,

- anomalous geochemistry without a unifying interpretation,

- repeated references to "interesting" alteration or structure,

- exploration programs that ended not with a negative conclusion - but with uncertainty.

In isolation, each of these signals is ambiguous.

At scale, they form a pattern:

systematic effort applied with systematically incomplete models.

In Western Australia, many districts now considered mature were preceded by long periods of apparent failure - until a new geological model, technology, or economic driver reframed the same ground.

Near-misses, in other words, are not mistakes.

They are the natural edges of evolving geological understanding.

Why National Archives Are Rich in Orphaned Opportunity

National geological archives - whether in Western Australia or Saudi Arabia - are uniquely suited to capturing near-misses.

They preserve:

- exploration rationales that were never commercially successful,

- early frontier thinking before deposit models stabilised,

- attempts made before today's economic or strategic drivers existed.

These archives are not biased toward success.

They are biased toward effort.

That makes them ideal hunting grounds for orphaned mines and forgotten prospects - provided the data can be analysed as a system, not as individual documents.

This is a fundamentally different use case from traditional data retrieval.

Why This Matters for Saudi Arabia - Now

Saudi Arabia's NGD bibliographic archive sits at a similar inflection point.

Much of its historical exploration was conducted:

- before today's critical minerals demand,

- before modern geophysical and geochemical resolution,

- before integrated, multi-dataset targeting workflows were feasible.

That does not imply missed discoveries.

It implies something more interesting:

the archive contains the edges of reasoning - the places where exploration logic stopped just short of synthesis.

While this near-miss framework has been validated in Western Australia, applying it to Saudi Arabia represents the next logical step - not as a shortcut to discovery, but as a way to systematically re-evaluate historical effort through modern lenses.

From Documents to Diagnostics

The shift required here is subtle but profound.

Instead of asking:

- What does this report say?

We ask:

- What does this report reveal about how the geology was understood at the time?

- What assumptions constrained follow-up?

- What evidence was present but unresolved?

When asked across thousands of reports simultaneously, these questions transform orphaned prospects from static records into diagnostic signals.

This reframing sets the stage for the synthesis approach we describe next - where historical exploration is no longer a graveyard of past attempts, but a structured map of learning, missteps, and unrealised opportunity.

Looking Ahead

The key takeaway is not that Saudi Arabia's past exploration "missed" deposits.

It's that historical exploration, when viewed through the lens of synthesis, becomes a strategic asset for future discovery - especially for commodities that were never the primary target of earlier campaigns.

The methodology exists.

It has been tested.

And it is now being extended.

Which brings us to the core question:

How do you scale this kind of reasoning - consistently, transparently, and across entire national datasets?

That is the problem Ghosts in the Machine was built to solve.

From Near-Misses to Synthesis: Ghosts in the Machine

By this point, a consistent pattern should be clear.

Historical exploration data rarely fails because information is missing.

It fails because insight requires synthesis — and synthesis never scaled.

Most systems are built to retrieve documents.

Some are built to rank relevance.

Very few are designed to reconstruct how geological understanding evolved — and where it stopped short.

Ghosts in the Machine is our name for addressing that gap.

Rather than treating reports as isolated records, the framework analyses exploration history as a sequence of decisions: what was tested, what assumptions guided those tests, and what evidence remained unresolved when programs ended.

In practical terms, this means shifting from asking:

- What does this report say?

To asking:

- What hypothesis was being tested?

- What constrained follow-up?

- What evidence accumulated without synthesis?

This approach does not aim to predict discoveries.

It aims to diagnose opportunity — by identifying where exploration effort consistently fell just short of understanding.

The reason this matters now is scale.

National geological archives preserve decades of exploration across commodities, economic cycles, and evolving models. They capture not just successes, but the edges of failure — the near-misses that precede breakthroughs.

For critical minerals in particular, this history is invaluable. Many were explored incidentally, described cautiously, or deprioritised before modern demand made them strategic. The signals exist — but only become visible when analysed as part of a larger learning system.

This synthesis framework has already been tested in mature jurisdictions like Western Australia. Extending it to new regions is not about transferring results — it’s about applying a proven way of thinking to different geological and strategic contexts.

Which leads to the final question:

If historical data can tell us where exploration almost succeeded, how should we be using it to guide what comes next?

That is the conversation we’re continuing — and the one we’ll be discussing at Future Minerals Forum.

What Comes Next at Future Minerals Forum 2026

If you're working with large exploration portfolios, national datasets, or legacy project ground, I'm currently booking meetings to discuss:

- A synthesis workflow proven on over a century of exploration data in Western Australia

- How that same approach is now being extended to Saudi Arabia

- What is already visible in the current RadiXplore Saudi dataset

- And how near-miss and orphaned project logic can inform next-stage targeting - without replacing geological judgment

These are working sessions, not product demos.

If you'll be attending Future Minerals Forum, or would like to connect ahead of time, feel free to reach out directly at contactus@radixplore.com